A solemn reminder that, as school board elections quickly approach, we, the people of New Mexico, must exercise our right to vote. Like any other election, it is important that we are able to elect school board candidates of our choice – people that we trust; who have our children's best interests in mind; who carry our values and understand our ways of life. Representation certainly matters.

Believe it or not, though, not every voter in New Mexico has that choice. Consider the scenario at a small school district in northwestern New Mexico where many Navajo parents cannot run for local school board or vote in the school district’s elections where their children go to school.

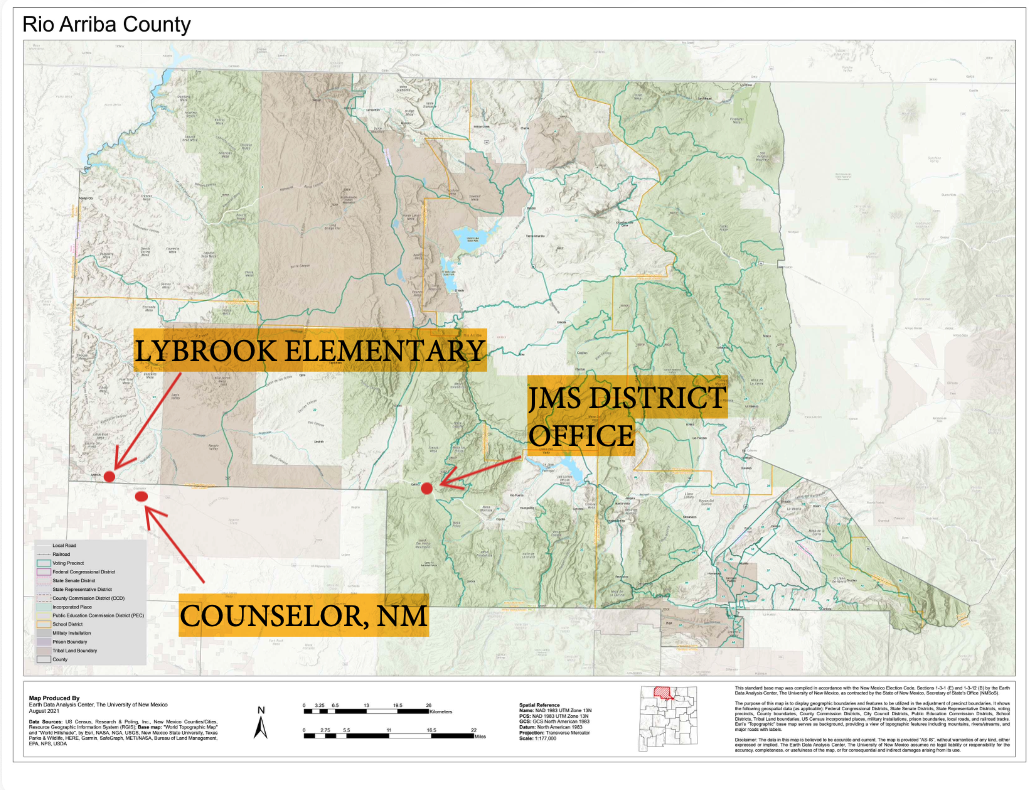

The Lybrook Elementary Problem

Tucked away in the rural southwest corner of the Jemez Mountain School District is Lybrook Elementary, a K–8 school on Highway 550 that serves around 70 students – all Navajo children. Many of those children, if not most, live in Counselor, New Mexico. Most of them catch the school bus to Lybrook Elementary, which is less than a three-minute drive away.

According to many parents and former staff, Lybrook Elementary is underfunded and under-resourced. Even while the district receives Impact Aid, Johnson O’Malley and other federal funds intended to offset certain challenges affecting, specifically, Native American students, Lybrook Elementary continues to be plagued by high-teacher attrition, numerous securityand safety hazards, and delipidated school buses. It took two years, for instance, to install a basic security fence around the campus. Other problems include the highly toxic air caused by gas and oil drilling nearby, leaving some students with a chronic cough.

"There's nobody at the school board meetings fighting for us or even taking in consideration of what Lybrook [Elementary] truly needs"

Remember: representation certainly matters! As of today, however, there are no Counselor parents or Navajo representatives on the Jemez Mountain School board. With the district's three other schools and administrative offices headquartered over 50 miles east, in Gallina, Lybrook Elementary students receive little to no support from a school board that not only lacks Counselor community’s trust and shared values but also fails to understand their children’s best interests and cultural ways of life.

And here's where borders and boundaries become a barrier to democracy. The school district's southern boundary runs contiguously along the southern boundary of Rio Arriba County. Counselor, however, sits about a quarter mile south of the school district boundary line, in Sandoval County. To vote in or run for Jemez Mountain School District’s school boardelections, however, you must live north of the same line that separates Lybrook Elementary from Counselor.

When Parent Advocates Are Silenced

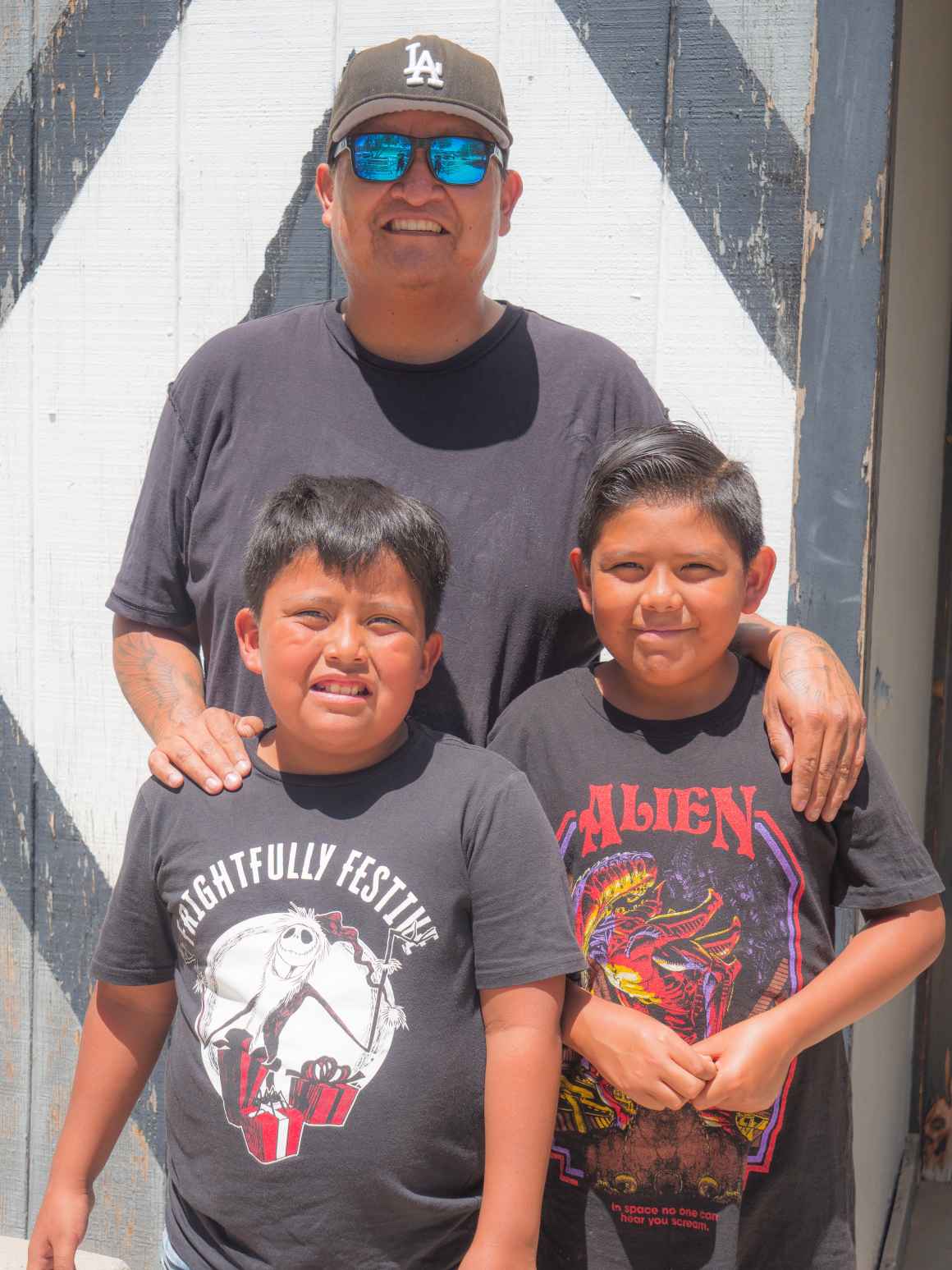

Meet Billton Werito: a widowed, single father of two sons attending Lybrook Elementary school; an enrolled member of the Navajo Nation and a U.S. Army combat veteran. About two years ago, Billton moved his kids from Bloomfield to Counselor. Almost instantly, he noticed problems at Lybrook Elementary.

"We have no representation on the school board," Billton said. "There's nobody at the school board meetings fighting for us or even taking in consideration of what Lybrook [Elementary] truly needs, because they don't see it on a day to day basis."

Faced with these issues, Billton did what any concerned parent would do: he got involved. Billton immediately began voicing his concerns at board meetings and with school district leaders. He was quickly elected president of the School District’s Indian Education Advisory committee and joined Lybrook's Parent Advisory Committee. He volunteered to help coachhis son’s basketball team. And on more than one occasion, he helped bring home his son’s teammates when their school bus broke down at an away game. His acclaim: superstarfather and stellar parent advocate.

In February 2025, however, the Jemez Mountain School District issued a trespass order against Billton and banned him from its properties indefinitely, alleging that he had violated school policies and had acted aggressively at past school board meetings. It was an unsuccessful attempt by the administration to fling mud and hope that something sticks. In October, Billton’s ACLU attorneys forced the district to rescind the trespass order on grounds that it violated his constitutional rights to assemble, associate and speak freely.

As of today, however, there are no Counselor parents or Navajo representatives on the Jemez Mountain School board.

Despite the lingering issues at Lybrook Elementary, Billton’s hope for his sons’ future remains the same – "graduate and go to college and get a degree and learn something in the world and come back and give back to the community to make our community better."

Locked Out of Democracy

What Lybrook Elementary needs is clear: a voice at the decision-making table. The ACLU of New Mexico will continue to monitor the lingering problems at Lybrook Elementary. We will also look for ways to create Indigenous and community representation on the district’s school board.

Watch the video to hear the stories of others interviewed, including a former Lybrook Elementary teacher, several parents, and the current vice president of the Navajo Nation. Their stories paint a fuller picture of a community that refuses to be silenced, even as the system tries to exclude them.