In April, the Trump administration began declaring parts of the U.S.-Mexico border region as “National Defense Areas” (NDAs), as if they were restricted-access military bases.

These NDA declarations aim to give the Department of Defense (DOD) new enforcement powers along the border. For immigrant communities, the stakes are especially high: crossing into an NDA now means risking federal trespassing charges in addition to immigration charges. U.S. citizens, too, may face prosecution if they enter poorly marked areas while traveling, hiking, hunting, or working near the border.

The creation of NDAs is part of a broader pattern in President Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant strategy and his efforts to push toward an unprecedented deployment of military power throughout the country. Communities are effectively cut off from access to public lands, while states are forced to grapple with heightened enforcement and diminished transparency.

Below we break down what the new “National Defense Areas” are, how they impact our rights, and how they harm our communities.

Where are the new “National Defense Areas”?

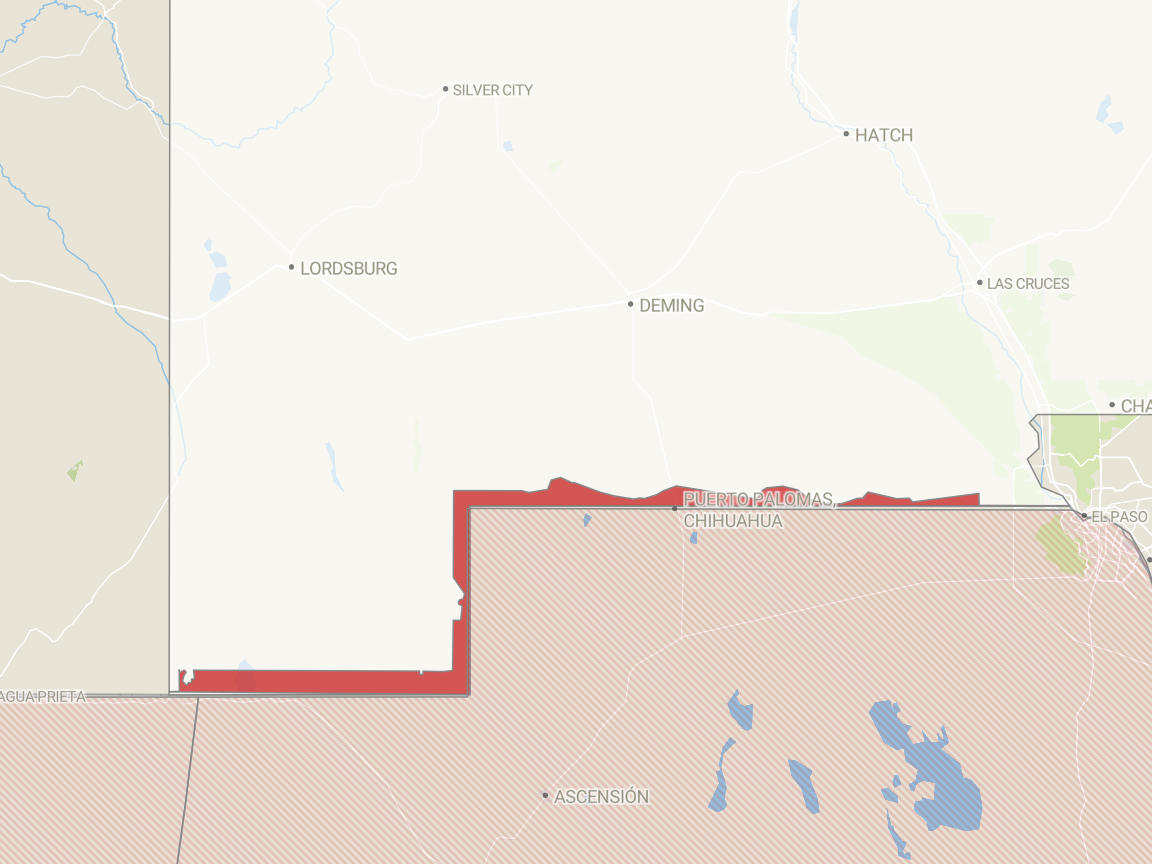

Earlier this year, President Trump issued a memorandum transferring control of certain federal public lands along the southern border to the DOD. The secretary of defense can now designate these lands as NDAs, and has already done so in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.

When describing the new areas, federal officials have typically sought to minimize their size by focusing on the inclusion of a narrow, 60-foot border buffer zone, known as the “Roosevelt Reservation,” which runs parallel to some sections of the U.S.-Mexico land border. However, in some areas the NDAs extend much farther north, encompassing highways, desert lands, and areas used by local communities.

For example the New Mexico NDA alone encompasses over 400 square miles, according to an analysis by Source New Mexico. The Texas NDA stretches for 63 miles, from El Paso to Fort Hancock. Other NDAs include those in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley and in Yuma County, Arizona. Each of them are characterized as military “installations” extending from — and often very far beyond — a specific military base.

The NDAs do not include land managed or owned by federally recognized tribes. Nor do they include non-federal land, such as state parks. However, if a person visits a state park or lives on tribal or privately owned land, and they accidentally cross into an NDA, they risk being stopped, questioned, searched, and wrongly accused of intentionally entering into the restricted area.

What power does the Federal Government assert in the National Defense Areas?

Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and its Border Patrol agents already surveil the region and have long-standing powers to question and arrest people who enter into the United States unlawfully. Inside NDAs, the government also asserts authority for U.S. troops to question, search and temporarily detain alleged trespassers. This risks blurring the line between civilian law enforcement and military authority.

What are the legal risks of entering a National Defense Area without permission?

Under federal law, entering one of these areas without permission can result in criminal charges for trespassing on military property, including:

- 18 U.S.C. § 1382 – entering military property without authorization. Punishable by up to six months in prison and a $5,000 fine

- 50 U.S.C. § 797 – willfully violating a security regulation for military property. Punishable by up to one year in prison and a $100,000 fine.

In recent months, people apprehended inside NDAs have already been charged under these laws.

How do the new National Defense Areas relate to immigration violations that the government might bring against noncitizens?

This depends on your citizenship status.

If you are a U.S. citizen:

- You cannot be charged with unlawful entry (or re-entry) to the United States under 8 U.S.C. 1325 or 1326, but you can still face federal trespass charges;

- You risk facing trespass charges if you cross into an NDA, for example when pulling off a highway, or hiking or hunting in desert lands.

If you are not a U.S. citizen:

- You face the same potential trespass charges, plus potential immigration charges, such as:

- 8 U.S.C. § 1325 – unlawful entry.

- 8 U.S.C. § 1326 – unlawful re-entry after deportation.

That means if a non-citizen is arrested within an NDA and is suspected of unauthorized entry into the U.S., they face the risk of three separate charges – unauthorized entry into a military property, willful violation of a security regulation, and unlawful entry or reentry.

If you are charged under 18 U.S.C. § 1382 or 50 U.S.C. § 797 for entering a National Defense Area, you have the right to a lawyer and the opportunity to challenge the charges in court. You are entitled to make the government prove its case against you. Anyone facing these charges should speak with an attorney as soon as possible for legal advice.

Are the NDAs clearly marked in order to prevent people from accidentally crossing into them?

No.

The government says it has posted warning signs, but the signs are small, only in English and Spanish, and few and far between. According to court filings, the signs are placed inside the NDAs, set back from the U.S.-Mexico border line, which means that people entering the NDA from Mexico have already crossed into the restricted area before having any opportunity to read the signs. The signs reportedly face south, which means that people entering the NDA from the north are unlikely to see any signs before crossing into the NDA.

Credit: Patrick Lohmann (SourceNM.com), Data: Bureau of Land Management and Defense (War) Department

A spokesperson for New Mexico Senator Martin Heinrich noted that the NDAs have “huge implications for anyone unwittingly driving along Highway 9 who might pull over to stretch their legs and unwittingly trespass on a military base.”

If you are near the southern border, exercise caution and try to avoid accidentally crossing into an NDA. Consulting visual maps may be helpful, but DOD has not published maps of each NDA and the available maps are insufficiently detailed to offer specific demarcations for people in the general vicinity.

Can I take photos or make a video of an NDA or an interaction with an official within an NDA?

Yes, but with caution.

Taking photographs and videos of places, people, and objects that are plainly visible in public spaces is a constitutional right—and that includes the exterior of federal buildings, and police, troops, and other government officials carrying out their duties.

However, under 18 USC § 795, Congress has made it a crime to photograph, sketch, map or draw “certain vital military or naval installations or equipment,” punishable by a fine or imprisonment of up to a year, or both. The DOD has posted signs near NDAs, citing this crime, implying that this law applies to these new areas.

The ACLU’s position is that when you are lawfully in a public space — including a public space adjacent to but outside the boundaries of a NDA or military installation — you have the right to photograph and take video of anything that is in plain view.

Do I still have constitutional rights in a National Defense Area?

Yes. NDAs do not strip you of your constitutional rights.

Fourth Amendment – Freedom from unreasonable searches and seizure

- Officers must have specific facts suggesting you broke the law to stop or search you.

- Race, ethnicity, or language alone are not valid reasons to detain you.

- You do not have to consent to a search. If asked, you can say “I do not consent.”

- If you are detained, ask why; officials should provide a reason.

Fifth Amendment – Right to due process

- You do not have to answer questions about citizenship or immigration status.

- Citizens are not required to carry proof of citizenship. Green card holders and visa holders must carry their immigration documents and show them if asked.

- If you wish to remain silent, say clearly: “I am exercising my right to remain silent.”

- Everyone in the U.S. has the right to contest charges against them, the right to due process and the right to seek advice from an attorney.

Sixth Amendment – Right to an attorney

- If you are charged with a crime, you have the right to an attorney – regardless of your citizenship status and ability to afford one.

- If you are stopped, detained, or arrested, you can tell the officer that you demand to speak with a lawyer.

With all that said, you should keep a few points in mind:

- No matter what your citizenship is, you should never provide false documents to an official.

- In the border area federal officials have greater latitude to board buses and to set up permanent or temporary checkpoints than they do farther into the interior of the US.

- Federal law permits Border Patrol to conduct certain enforcement activities, such as entering a vehicle, without a warrant “within a reasonable distance” from the border. The government defines this distance to be 100 miles. The southern border NDAs fall within this “100 Mile Zone.”