The reopening of a troubled immigrant detention facility in Torrance County helped the private prison company CoreCivic increase revenues by nearly $19 million last year, the company said in financial filings.

The late 2019 reopening was praised by Torrance County officials, but since then a failed government inspection, understaffing, and reports of abused detainees have raised questions about the facility’s management and positive impact on the county.

The Torrance County Detention Facility (TCDF) in Estancia had been vacant since late 2017. In 2019, county officials approved a new contract with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, with the agency paying nearly $2 million a month to Tennessee-based CoreCivic for running the facility. The contract, elected officials said, would help bring jobs to the rural community.

But CoreCivic’s Annual Report suggests the facility has mostly been lucrative for CoreCivic itself. The company said reopening TCDF bolstered annual revenues by $18.6 million in 2020 compared to the previous year.

In July 2021, the facility failed an annual — and notoriously lax — inspection by an ICE contractor. Inspectors found TCDF was severely understaffed, saying “the current staffing level is at fifty percent of the authorized correction/security positions. Staff is currently working mandatory overtime shifts.” Inspectors also found unsanitary food, failures in tracking grievances and deficient visitation rules at the facility.

Earlier this year, the ACLU of New Mexico filed a lawsuit with the New Mexico Immigrant Law Center on behalf of nine former Torrance detainees and the Santa Fe Dreamers Project against CoreCivic and Torrance County. The lawsuit alleged that CoreCivic sprayed the men with chemical agents in response to a peaceful hunger strike. The men were protesting inadequate precautions against COVID-19, poor living conditions, and the withholding of status updates on their immigration cases.

CoreCivic, however, portrayed the reopening of TCDF as a success story in its efforts to maintain and grow its government clients, which the company relies upon to keep beds full and generate corporate profits. Many of the individuals in the for-profit facility are people seeking asylum. The 910-bed TCDF facility primarily holds people in administrative ICE detention, as well as a small number of people arrested by the county and the U.S. Marshals Service.

Despite reports of abuse, from May 2020 through May 2021, ICE used taxpayer money to pay CoreCivic $1,993,449 per month for a guaranteed 714 beds at TCDF, regardless of how many people were detained at the facility. In fiscal year 2021, TCDF had an average daily population of just 152 people, according to data from ICE.

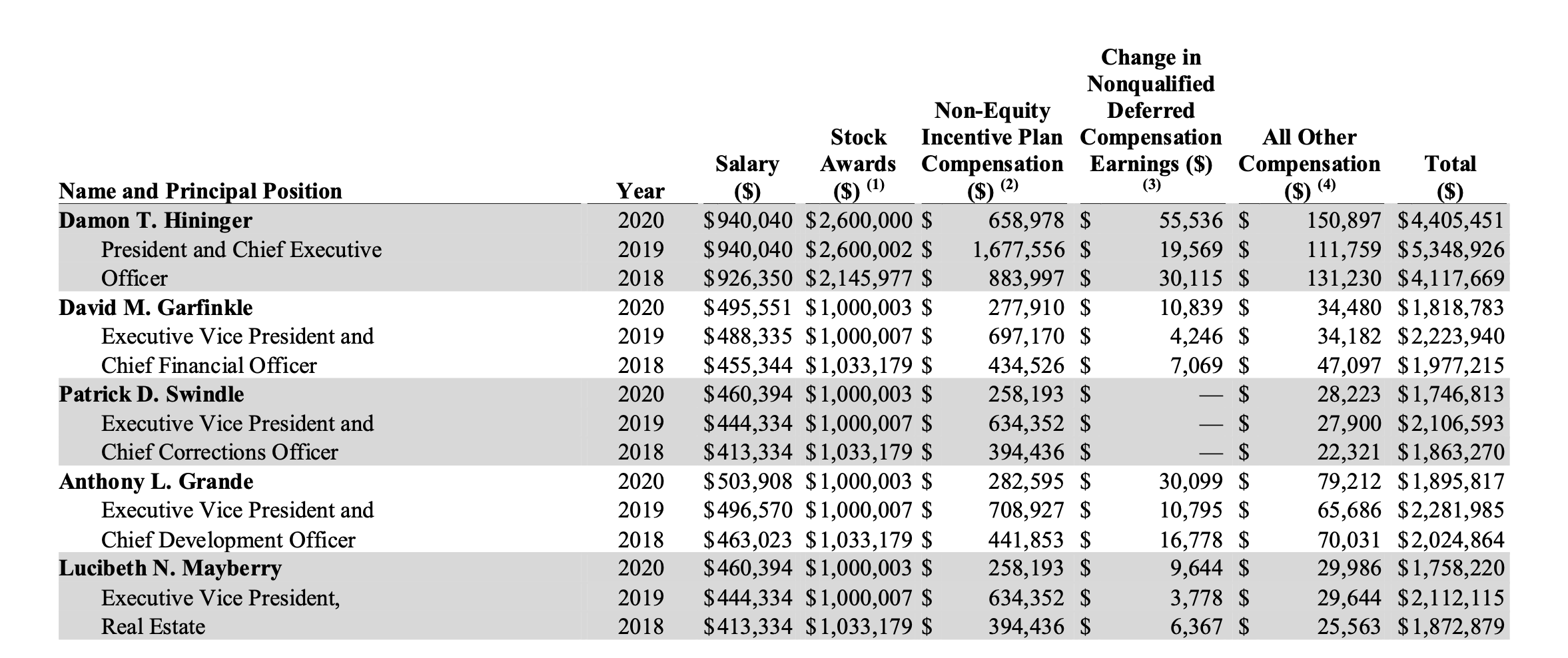

Where do these revenues go? And whose paychecks do they cover? According to records obtained by the ACLU of New Mexico, a CoreCivic detention officer at TCDF earns an hourly wage of $16.73, equivalent to less than $35,000 per year. CoreCivic CEO Damon Hininger, meanwhile, was paid more than $4.4 million in total compensation in 2020. Other top executives were paid more than $1.7 million each.

To the public, CoreCivic touts its mission as providing “high quality, compassionate treatment to all those in [its] care.” But in a message aimed at its investors, the company states its “primary corporate objective is creating long-term value for our stockholders by pursuing avenues to profitably grow our primary CoreCivic Safety correctional and detention business while diversifying our revenues and cash flows . . .”

And what about the detained individuals from whom this profit flows? Among the asylum seekers recently held at TCDF, many are Haitians who fled the climate disasters, economic disrepair, and political turmoil of their home country to seek safety and rejoin loved ones. After enduring treacherous journeys and exercising their legal right to request protection in the United States, they found themselves in a rural New Mexico carceral setting far from public view and access to counsel.

Despite Torrance County’s initial excitement for new jobs, TCDF continues to struggle with chronic understaffing. Among CoreCivic’s numerous job listings for the detention center are six unfilled or underfilled categories of medical and mental health care positions. To maintain the short-staffed facility, CoreCivic relies on detained individuals to work in positions such as food service and housekeeping.

Their pay? $1 per day.