Shane Lasiter is a 57-year-old man, who until recently, had been in prison since he was sixteen years old. He’s only been a free man for two short months, but he’s already busy volunteering as a mentor at La Plazita Institute encouraging young people to make healthy life decisions. He knows all too well how a lack of guidance can lead youth to make poor decisions that have dire and lasting consequences.

"I started hanging around not so good people, so I became a not so good person. And I got in trouble."

Shane spent most of his formative years against a backdrop of family instability and transience. Between the ages of 10-16, Shane’s family moved to five different states and he attended 12 different schools. He says turmoil entered his life around fifth grade.

“I became the kind of kid who would run away,” said Shane. “The police were always looking for me.”

Reflecting on the mistakes of his youth, Shane said, “I was kind of guided by what I thought my peers expected of me. I started hanging around not so good people, so I became a not so good person. And I got in trouble.”

In 1981, when Shane was still just a child, he was sentenced to life in prison for his involvement in an armed robbery and killing of a local restaurant owner. Shane spent the next forty years of his life behind bars. Though he did much to turn his life around -- participating in several educational programs, training service dogs, and caring for fellow incarcerated people -- he also experienced serious trauma. The experience of coming of age in prison has marked him.

The Problem with Extreme Youth Sentencing

Shane’s story is not unique. Despite extensive research that youth who commit serious offenses show promise for rehabilitation, the United States still subjects thousands of children to extreme sentences, such as life in prison. For most of these youth, the only real chance for release and to be reunited with their families comes from parole. However, people incarcerated since their youth are routinely denied parole, long after they’ve grown, matured and been rehabilitated, and in many cases, solely because of the crime they committed in their youth—not because of who they are now.

The United States remains the only country in the world that allows children to be sentenced to life without parole.

ACLU research has found that in 12 states alone, over 8,000 people are serving a sentence of life or 40 or more years for a crime committed under the age of 18.

The United States remains the only country in the world that allows children to be sentenced to life without parole. In the last decade, two U.S. Supreme Court rulings significantly restricted this practice, reasoning that children age out of criminal activity and have greater capacity for reform. In a recent decision, the U.S. The Supreme Court declined to extend these restrictions further, saying that it is up to the states to make the necessary policy decisions to protect children from extreme punishments. Many states already have. Today, 25 states and D.C. ban life without parole for children. Many of these same states have created early review opportunities for those serving long adult sentences for crimes committed when they were children. New Mexico is behind in this trend.

New Mexico still has not banned the imposition of life without parole on children, and many children are serving long adult sentences that deprive them of an opportunity for review at a developmentally appropriate time. There are nearly 100 people serving sentences longer than 10 years for crimes committed as children. Many are serving sentences that practically guarantee that they will spend the rest of their lives in prison. Many have already spent decades in prison for crimes committed when they were 15 and 16 years old.

Parole Board Rule Change Shows Progress

Momentum for change is building. This year, the ACLU of New Mexico worked with the New Mexico Adult Parole Board to update their procedures for those serving life sentences for crimes committed when they were children in accordance with new constitutional standards and the advances in adolescent brain science upon which those new standards are based.

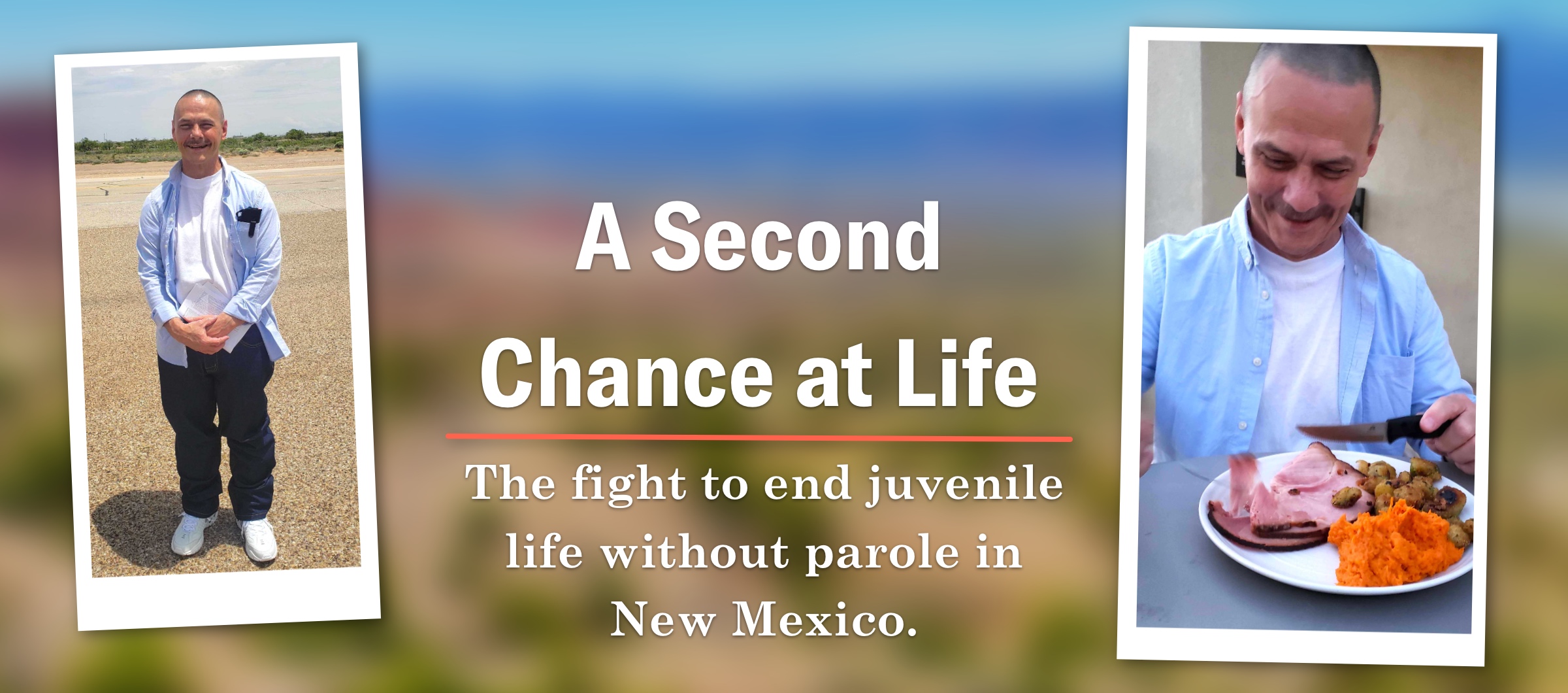

Photo Left: Shane Lasiter eating his first meal after leaving prison after decades behind bars.

The new rule, passed in March of 2021, provides for access to counsel during hearings and directs the board to focus on age at the time of the offense and growth, maturity, and rehabilitation since then.

Prior to the rule change, the Parole Board denied Shane’s release five times. It didn't matter that he spent the vast majority of his years incarcerated atoning for his mistakes of the past.

"For those serving sentences for crimes committed when they were children, these proceedings were categorically unconstitutional."

“The first time I went in front of [the parole board] I didn’t expect them to say yes because I’ve seen New Mexico at work for so long. I was hopeful but didn’t really expect anything,” said Shane. “But the second time, I did. I thought I had all my ducks in a line and I was ready.”

Shane told the board all about the changes he’d made in the years since he was sentenced. He left hopeful. But ten days later he received another notice of denial. He didn’t get an explanation about why he was denied or what he needed to work on to be granted parole.

“For years, New Mexico’s parole board had one of the lowest grant rates in the nation, said Denali Wilson, Legal Fellow at the ACLU of New Mexico. “For those serving sentences for crimes committed when they were children, these proceedings were categorically unconstitutional.,” said Denali Wilson, Legal Fellow at the ACLU of New Mexico.

In the first hearing under the newly adopted rule, Shane was finally granted parole and released from prison after 40 years.

While the rule change improves the process through which a child serving a life sentence is considered for parole once they are eligible, legislative action is needed to change the timing of eligibility for a parole hearing. Under existing law, a child serving a life sentence does not become eligible for parole until he or she is well into their 40s.

The Path Forward

Last legislative session, the ACLU of New Mexico supported a bill to abolish juvenile life without parole in New Mexico and create early eligibility for parole for those serving long adult sentences for crimes committed as children. Though the session ended before the bill was heard for a vote on the House floor, the ACLU of New Mexico will continue to fight for fair and age appropriate sentencing reform in New Mexico.

“All children are capable and worthy of redemption,” said Wilson. “We need legislation that provides a second chance to young people who have grown into different people, are committed to repairing the harm they caused, and are ready to safely rejoin society.”

Shane is steadfast in his commitment to accounting for the mistakes of his youth and being the best person he can now that he is free. Yet, he was almost denied this opportunity. His story is a testament to why we must continue to create new policies that are grounded in science and humanity.

“I went through a lot of hardships and trauma and learned to grow and develop in [prison],” Shane said. “No matter the pressure or loss or suffering, no matter the hopelessness, there is hope. Just keep getting up. Just keep moving forward.”