As legislators earlier this year debated closing New Mexico’s numerous private prisons and immigration detention centers, an Otero County official made the case for sparing a controversial detention facility in his county.

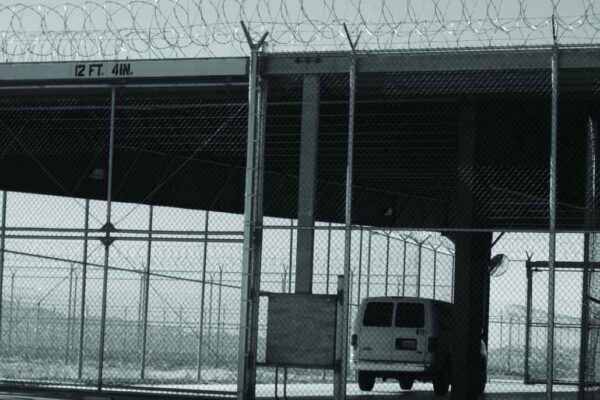

The Otero County Processing Center (OCPC), which holds men detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), couldn’t close because it was the only source of revenue to pay off tens of millions of dollars in bond debt, County Attorney Michael Eshleman told legislators and reporters.

Closure would risk defaulting on the bonds, hurting the county’s credit and dealing a “significant blow to the county budget,” Eshleman told The NM Political Report.

But Reilly White, a public finance expert who recently reviewed Otero County’s bond filings, painted a markedly different picture. The county is under no obligation to pay back those bonds if the facility closes, the expert said, and a default would have little, if any, impact on its credit rating.

The facility provides about 3 percent of the county’s annual revenues.

Otero County’s bond obligation has been “a critical piece” in efforts to close OCPC, said Rep. Angelica Rubio (D-Doña Ana), who co-sponsored a bill earlier this year to close privately-run facilities in the state. The facility has been dogged for years by allegations of unsanitary conditions, medical neglect and mistreatment of detainees.

“Part of the reason we weren’t able to gain the kind of support we would’ve wanted this past session was because of the lobbyist for the Otero County facility using the bonds as a reason to not target the facility,” Rubio said.

Eshleman has since left Otero County. County Manager Pamela Heltner did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Criticism of OCPC, which is run by the private Utah-based Management & Training Corporation (MTC), has been growing for years. In 2017, a Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General report found moldy bathrooms and broken telephones at the facility, as well as frequent, unjustified use of solitary confinement. One man told inspectors he was placed in solitary for multiple days because he shared coffee with a fellow detainee.

The problems at OCPC and four other facilities reviewed “undermine the protection of detainees’ rights, their humane treatment, and the provision of a safe and healthy environment,” the report said.

A study published this year by nonprofits Advocate Visitors with Immigrants in Detention (AVID) in the Chihuahuan Desert and Innovation Law Lab found two-thirds of detainees at OCPC who spoke to legal advocates had problems with the facility. More than half of the complaints were about access to medical care or due process violations.

Over the years, people detained there have reported bad food, harassment of LGBTQ individuals, difficulty accessing attorneys and more, said Nia Rucker, policy counsel at the ACLU of New Mexico.

“The abuse is beyond just the food and the conditions,” Rucker said. “It also goes to the staff, and it goes to all the actors that are involved in someone’s stay and detention that are not really taking care of people.”

An MTC spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

‘An unsolicited proposal’

OCPC is not Otero County’s first foray into for-profit detention. In 2003, the county built a prison facility -- also run by MTC -- to detain people picked up by county officers and the U.S. Marshals Service, among others.

Then, in October 2006, Otero “made an unsolicited proposal to ICE regarding the County’s ability to provide additional detention space,” the county’s bond document states. ICE was interested, and the following year Otero submitted a detailed proposal for a 1,096-bed facility matching ICE’s specifications.

The facility was to be paid for with a $62.3 million revenue bond, a financial tool that began growing in popularity throughout the country in the early 2000s, UNM Associate Professor of Finance Reilly White said.

Traditional bonds, called general obligation bonds, are paid with a city or county’s tax revenue and generally require a public vote. Revenue bonds, on the other hand, are paid exclusively by the revenue generated by the particular project they’re funding. And because taxes are not on the line, they don’t require a public vote.

“The implementation of these various sentencing alternatives could negatively impact the supply of prisoners which could be incarcerated in the Facility.”

The trade-off for protecting the county’s taxes is a higher interest rate. The OCPC revenue bonds were originally issued with a 9 percent interest rate, White said, compared to a likely interest rate between 3 and 5 percent for a similar general obligation bond.

“That’s an extraordinarily expensive bond for financing purposes and it implies there’s a lot of risk in bonds like these,” he said.

The risk was outlined in the bond itself, which said the profitability of the facility depended on there always being more people detained than there is space to hold them.

Work release programs and tools like GPS monitoring presented a financial risk for investors who bought the bonds because “The implementation of these various sentencing alternatives could negatively impact the supply of prisoners which could be incarcerated in the Facility.”

Outstanding debt

In January, Otero County’s then-attorney Eshleman said that without the contract with ICE, the county would be left with $58 million in outstanding bond debt, according to the Santa Fe New Mexican.

Otero budget documents show about $45.2 million are still due on the bond between now and 2028.

Were OCPC to close tomorrow, White said, an account set up for paying back the bonds has enough reserves to keep making payments while the county decides what to do next.

“This would involve, my guess would be, a herculean effort by county officials as well as federal officials to say let’s look at this,” White said, “can we repurpose this prison for taking state inmates or something else?”

Like a home bankruptcy, if that process failed the property would likely go up for sale, with that money going to pay back bondholders. The difference between the sales price and the outstanding bond debt would be a loss for investors who purchased the bonds.

There would be no obligation for the county to use tax money to pay off the bonds or the difference between the sale of the property and the remaining debt.

As to whether that would affect Otero County’s credit rating, “The short answer is not directly,” White said.

If the county decided to take out general obligation bonds paid for with taxes to purchase the facility, that could have an impact on its credit rating, he said. The loss of income from the facility could also play a role, although revenue is only one of the factors, along with county management, outstanding pension obligations and the overall tax base, that go into credit ratings.

“The real reason they want to keep it open is so they can continue making money, regardless of the human costs that result.”

Since fiscal year 2018, Otero County has received almost $1.3 million in revenue from OCPC, less than the nearly $2.3 million it has made from the prison facility also managed by MTC, according to county budget documents. Last fiscal year, OCPC brought in $457,730 to the county, roughly 3 percent of its total revenues.

“Otero County actively sought out a way to profit off of human misery and succeeded in making over a million a year,” said Katie Hoeppner, communications director at the ACLU of New Mexico. “The real reason they want to keep it open is so they can continue making money, regardless of the human costs that result.”

Kristin Greer Love, a Central New Mexico Community College teacher and policy attorney who has worked on ICE detention in the state, pointed out that the facility could actually be a financial liability for the county.

“If they had one lawsuit, that could totally wipe away years from financial gains from this horrible, cruel detention center,” Greer Love, who previously worked at the ACLU of New Mexico, said.

At the same time, she said, the jobs created by ICE detention centers tend to be difficult, unattractive and low-paying.

“It seems to me (Otero) could invest in something else,” she said, “that would be better for everyone.”

Contact Invesitgative Reporter Leonardo Castañeda at [email protected]