In its recent editorial (July 29), the Albuquerque Journal suggests that in the wake of federal judge Robert C. Brack’s ruling that the Albuquerque “Pedestrian Safety Ordinance” violates the First Amendment, the city of Albuquerque can still somehow “walk the line” on safety and free speech.

But let’s get real. Albuquerque’s “public safety” ordinance was always an anti-panhandling law dressed up in public safety clothes, not a serious attempt to improve pedestrian safety within our city. The public safety fig leaf looked extra skimpy from the start, given that the city tried to pass an ordinance in 2004 that explicitly banned panhandling in certain parts of Albuquerque. This law, too, was struck down by the court as unconstitutional.

That’s the real problem here. The city can’t “walk the line” because the intent was always to drive the most vulnerable and desperate in our community out of public spaces where they are most visible. Any ordinance that has the primary intent and effect of suppressing the visibility of people in poverty is almost guaranteed to run afoul of the First Amendment.

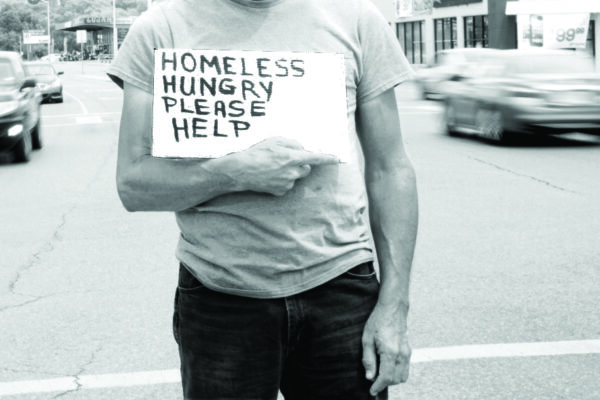

Simply put: Poor people have the right to exist in public spaces. And if that makes us uncomfortable, if it makes us angry to see, then good. It should cause us discomfort; it should make us angry that we, the richest and most powerful nation that has ever existed, have insufficient political will to address the structural causes and underlying drivers of poverty.

And let’s be clear: Criminalizing poverty only makes the problem worse. Handing out fines to people who can’t afford to pay them is just a recipe for plunging people deeper into poverty and desperation. Arresting people for asking for help only endlessly cycles people in and out of the criminal justice system at taxpayer expense. We can’t punish our way out of this problem, and we can’t sweep it under the rug.

This most recent ruling should convince the city that there is no legal path forward for these kinds of panhandling laws, as the Journal suggests there might be if only the city would do a better job “mining its horrifying pedestrian death statistics” to provide evidence that the next incarnation of the law is actually oriented toward improving public safety. If they could have, they would have done so already. Attorneys for the city had ample opportunity to provide convincing evidence to the court that people standing on medians or near street corners is a serious threat to public safety, but they had nothing to offer but speculation.

Indeed, out of hundreds of pages of evidence presented in the case, the city could point to only four pedestrian/vehicle conflicts in the past four years that clearly involved someone standing on a median or ramp, who was not otherwise likely violating an existing law. Furthermore, a 2016 study conducted by the University of New Mexico on improving pedestrian safety in Albuquerque makes no mention of panhandling as a significant concern, instead listing recommendations as public education campaigns, safer crosswalks, and better lighting as the most important things the city can do to make pedestrians safer. Quite simply, there is no link to people panhandling in medians and Albuquerque’s high rate of vehicles hitting pedestrians.

Albuquerque should abandon its pursuit of anti-panhandling ordinances, like many other municipalities around the state have recently done, and focus its efforts on real traffic safety solutions for the people of our city. After experiencing a close call recently on a crosswalk Downtown, I, for one, would greatly appreciate it.

This op-ed was originally published in the Albuquerque Journal.