Twenty-One Shots

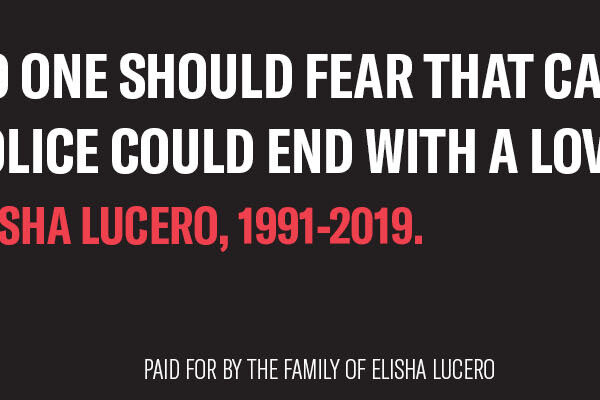

Elisha Lucero had long suffered from persistent and intense migraine headaches, but it wasn’t until her car wreck she learned the true cause. In December 2017, when she was taken to the hospital emergency room for imaging following the wreck, the CAT scan revealed a large tumor growing inside her skull, creating intracranial pressure that restricted the flow of blood out of her brain. She went into surgery in June 2018 and the surgeons were able to successfully remove the tumor. But afterwards, things were never quite the same.

“Elisha was a very compassionate, loving individual,” said Elaine Maestas, Elisha’s older sister. “She was always the life of the party. She had a smile that would brighten up the room. She was one of the most giving, selfless people I’ve ever known. It didn’t matter if you were a friend, family member, or a stranger—if you needed her, she would drop what she was doing and help you in a heartbeat.”

“But unfortunately, after the surgery, things began to go rapidly downhill and her symptoms increased in severity,” recalls Elaine. “She would get head-aches and slur her speech sometimes; she would forget the words for things. She couldn’t get her words out right.”

"Elisha was a very compassionate, loving individual. She was always the life of the party. She had a smile that would brighten up the room."

The headaches became so severe that Elisha sought emergency help at the hospital on multiple occasions, and in May 2019 family members noticed drastic changes in her behavior. She began experiencing hallucinations and seizures and exhibited symptoms of psychosis. Alarmed by the rapid deterioration of her mental and physical health, Elaine arranged for a medical appointment for Elisha in August to address her sister’s concerning post-operative behavior. She never made it to the appointment.

Early in the morning of July 22, Elisha’s erratic behavior escalated. Around midnight, Elisha, in an agitated state, entered her uncle’s home in Albuquerque’s South Valley where she was staying in her RV and hit him without provocation or explanation.

“My sister wasn’t the kind of person who would do that,” recalls Elaine. “My Uncle just told her to go back to her RV to calm down. They got her to go back inside the RV and tried calling me before he called the police because I could usually talk to my sister.”

Tragically, Elaine’s new house in the village of Tijeras in the mountains east of Albuquerque had poor cell coverage and they were unable to reach her. As a last resort, Elisha’s cousin called 911 and asked for the authorities to intervene, as they had done the previous month when Elisha herself called for emergency assistance during a separate mental health crisis.

Three Bernalillo County Sheriff’s Office deputies arrived at the scene, including a deputy who had responded to Elisha’s plea for help the previous month. Unlike the prior incident, however, the deputies did not call for a Mobile Crisis Unit Team (MCUT), a law enforcement unit composed of social workers and deputies with specialized training in helping people who are experiencing a mental health crisis. Despite the foreknowledge that Elisha Lucero suffered mental health problems, the deputies not only failed to call a MCUT to assist, they escalated the situation by banging on the door, shining their flashlights through her windows, yelling commands, and brandishing weapons outside her RV.

It’s impossible to know what Elisha was thinking or feeling in that moment and state of mind, but accounts of her reactions to the deputies’ aggressive actions outside her home that night are consistent with someone in a panicked or disoriented state. Agitated, she paced back and forth inside her RV, still half-undressed for bed, while recording the deputies outside on her cellphone. As the deputies prepared to leave her a court summons, she burst out of her RV and ran outside nude from the waist up. All three deputies opened fire.

For me, I’ll never understand why they shot my sister 21 times. My sister was four-foot, eleven inches tall – the size of my eleven year old daughter. I don’t get that.

The deputies riddled her diminutive frame. The coroner later reported she suffered from 34 individual wounds, caused by 21 separate gunshots. None of the deputies present attempted to render aid after the shooting, and she was pronounced dead at the scene.

The BCSO deputies later claimed that they opened fire because Elisha was holding a kitchen knife when she exited the RV, an allegation disputed by Elisha’s cousin who witnessed the incident from only a few feet away. However, since none of the deputies present at the shooting were equipped with body worn cameras, no corroborating evidence exists to shed light on what actually happened the night Elisha Lucero was killed.

“For me, I’ll never understand why they shot my sister 21 times,” said Elaine. “My sister was four-foot, eleven inches tall – the size of my eleven year old daughter. I don’t get that. The county is failing their deputies by not training them correctly. These men clearly did not know how to respond that night. My sister would still be here if they knew how to respond. And that's the hardest thing for us."

BCSO's Campaign Against Transparency

The Bernalillo County Sheriff’s Office is one of the only law enforcement agencies of size in the state of New Mexico that has yet to equip their field officers with body-worn cameras to record interactions with the public. These recording devices have become standard equipment for most law enforcement agencies in the United States, with 58% reporting their use by 2018. Benefits of the technology include greater transparency in incidents where officers use force, increased accountability, quicker resolution of citizen complaints, and the ability to collect data for training purposes.

“Using officer-worn camera technology should really be a no-brainer for law enforcement agencies,” said ACLU of New Mexico Legal Director Leon Howard. “These tools make it safer both for the officers who wear them and the public they serve. Body worn cameras, when paired with robust and consistently enforced policies regarding their use, provide a clearer and more transparent account of a use of force incident. Video evidence can be an important factor in corroborating an officer’s testimony, or it can be instrumental in revealing serious wrongdoing. Oftentimes the mere knowledge that interactions with the public are being recorded is enough to help slow things down and prevent dangerous escalation.”

Despite the many and manifest benefits of body worn cameras, BCSO Sheriff Manny Gonzales has steadfastly refused to equip his deputies with them. Even in the face of widespread evidence to the contrary, Gonzales has asserted that bodyworn cameras will do nothing to improve transparency and accountability in his department, and even went so far as to claim that body worn cameras would be a “distraction” for his deputies. When the Bernalillo County Commission allocated half a million dollars in April 2019 to begin equipping the department with body worn cameras, Sheriff Gonzales refused to use the funds as allocated, stating that, “They have no business telling us operationally what we will use for this department.”

"Oftentimes the mere knowledge that interactions with the public are being recorded is enough to help slow things down and prevent dangerous escalation."

Meanwhile, people living in Bernalillo County have watched with growing alarm as BCSO’s officer involved shootings spiked in recent years, with an accompanying rise in lawsuits against the agency. In 2017, BCSO deputies opened fire on two unarmed men suspected of stealing a vehicle, killing both. The incident resulted in three seperate civil lawsuits, costing county taxpayers $1.8 million dollars in settlements. The incident was only one of nine officer involved shootings for BCSO that year.

After the shooting of Elisha Lucero, the simmering dissatisfaction with BCSO’s lack of accountability boiled over. Led by Elaine Maestas and other Lucero family members, Bernalillo County residents came together to demand that Sheriff Gonzales equip his deputies with body-worn cameras and implement better training and protocols for dealing with people experiencing a mental health crisis.

In October of 2019, the Bernalillo County Commission responded to the public outcry by unanimously approving a resolution recommending that BCSO “implement a plan to purchase, install, use and manage dashboard and lapel cameras.” The commission allocated $1 million for body cameras in seed money, along with a recurring allocation of a further half million annually. But due to the unique nature of the Sheriff’s office, an independently elected public official accountable primarily to voters rather than the commission, the commission found itself limited in its ability to compel BCSO to actually use the funds as allocated. After arguing against the resolution before the commision, Sheriff Gonzales remarked to the press following the vote that he is “always willing to have discussion [about body cameras], but it doesn’t mean I’m going to move my position.”

The Price of Bad Policing

The ACLU of New Mexico has been at the forefront of law enforcement accountability efforts since its founding in the early 1960s, and in the last decade has been a leader in the community movement to reform the Albuquerque Police Department’s use of force policies following a spree of officer involved shootings. The ACLU of New Mexico has also been one of the loudest voices advocating for BCSO to join the 21st century by equipping its deputies with body worn cameras. Following Elisha Lucero’s death, the ACLU of New Mexico immediately connected with Elaine Maestas and the Lucero family to amplify and support their efforts to bring greater transparency and accountability to BCSO.

“When she first died, my thought was, ‘How can this happen to her?’,” recalls Elaine. “How can I change things so this never happens again? So I came to the ACLU and learned how they’d been advocating for lapel cameras; and that’s how my journey started. I started going to each one of the commision meetings, speaking out to say ‘We need to hold those who serve us accountable. There has to be a level of transparency we don’t have right now. It’s not fair to the public. It’s not fair to the deputies. Transparency benefits all of us.’”

In cooperation with the Lucero family, the ACLU of New Mexico mobilized its supporters to pack Bernalillo County Commission meetings to demand implementation of body worn cameras, spoke out forcefully for needed reforms in the media, and organized a groundswell of online support for transparent policing in Bernalillo County. Even the Albuquerque Journal, not well known for its pogressive editorial stances, came out strongly against Sheriff Gonzales’ stubborn refusal to equip his deputies with cameras.

"There has to be a level of transparency we don’t have right now. It’s not fair to the public. It’s not fair to the deputies. Transparency benefits all of us."

Despite this overwhelming pressure from county residents, the commission, and the press, Sheriff Gonzales has remained steadfast in his refusal.

“It’s extraordinarily frustrating,” said Howard “Because of how the system is structured, there is little opportunity to hold a Sheriff accountable outside of the ballot box. In our increasingly polarized political environment, we’re seeing more and more Sheriffs become rogue actors, not just here in New Mexico, but across the United States.”

Though Sheriff Gonzales appears to feel immune to public pressure, he and his department are still subject to the rule of law and the courts. In November 2019, the ACLU of New Mexico and civil rights law firm Kennedy Kennedy & Ives (KKI) filed a civil lawsuit on behalf of Elaine Maestas and the Lucero family demanding that the county pay damages for their role in Elisha’s wrongful and entirely avoidable death. In an unusual move, the county chose to enter into settlement negotiations only four months after the filing of the suit. In March 2020, the ACLU of New Mexico and KKI settled the lawsuit with the county for $4 million, one of the largest settlements of its kind in New Mexico.

“This settlement should come as a wake up call for the Sheriff,” said Laura Schauer Ives, KKI partner and ACLU of New Mexico cooperating attorney. “The department needs to commit to better training, transparency, and accountability moving forward. If they insist on maintaining the status quo, families will continue to suffer needlessly and taxpayers will continue to foot the bill.”

The settlement is not the end of the fight for Elaine and the Lucero family however. They remain committed to working with the ACLU of New Mexico to bring lasting reform to BCSO, including equipping all deputies with body cameras, implementing better officer training, and dismantling the department’s culture of aggression.

“We want to keep this from ever happening to someone else’s family member,” said Elaine. “That’s why we’re advocating the way we are. I can’t change what happened to my sister, and that breaks my heart. But if I can help prevent someone else’s Elisha, and someone else’s family from going through what we’ve been through I’m going to do it. That’s why we’re fighting: to honor her.”